Simorgh Recites

May 29 2015

Eskandari’s Butterfly Stickers There is a simultaneous sense of futurity and historicity in the five large canvas paintings, and one video work, by artist Mohammad Eskandari. His superb mastery over the brush comes from having been born into an artistic family as well as a successful artistic education and career. Yet, these images are not merely an outcome of skill and upbringing. Through that inheritance, these works convey a deep insight into Iranian history, Iranian symbolism, Iranian modernity, Iranian wealth, and Iranian pain. On these canvases, Eskandari embraces the Qajar and Pahlavi pardeh khani tradition. An old Iranian artistic method, that I would trace even further back to Sassanian rock-cuts, portable paintings on large canvases (pardeh) used to illustrate the Battle of Karbala, Koranic stories, and the epic of the Shahnameh. Reviving the large-scale technique, the artist invokes other forms of historical accounts that speak so clearly about a tentative future. Thus, Eskandari selects fragments of rich architectural and geographic past: a gate, an Eyvan, a summit, and a forest collide into a future shaped by human agency that remains unresolved. Historical monuments, national symbols, fragments of natural landscape, and separate figures all hover on the painterly surface – somehow in a state of constant flux, a state of abstraction and foolishness that makes total sense. The painter speaks to his audience. The painter invites his viewer to inhabit a space of ambivalence and absurdity… a place that goes somewhere but that is certainly irresolute.

The gates of Tehran University, designed in 1965 by Kurosh Farzami, himself a student of the university’s fine arts faculty, has become a loaded symbol for so many ideologies. For Eskandari the gates no doubts are also a part of personal stories. “The roots of these collages are in my childhood games and the figures … reference stickers.” Appropriated and re-appropriated as architectural icons, the gates reappear as a backdrop to Eskandari’s three figures. A solider. He looks like a transplant from 1979. Two rather silly male figures flank him. He is policing them; they are engaging the viewer as if inviting her to come in. To join the play, the game, the fight. There is a profound pain and gravity in this folly. It is as if it is a matter of life and death, much like for a child a world made and remade with stickers.

Considered one of the oldest mosques in Iran, the Tari Khaneh in Damghan was completed in 750-89. With its uniquely large barrel vault, it was probably built on a Sassanian fire temple as Persia passed to Muslim rule. It is on the background of the great Eyvan that Eskandari implants his three modern figures. As the other two, a female figure absurdly jumps into the air. Cello in hand. Anachronism. Temporal anachronism. A cello? The paramount symbol of Western classical music. Yo Yo Ma. But also a spatial anachronism. A cello in a mosque. Yet the sky is crystal blue.

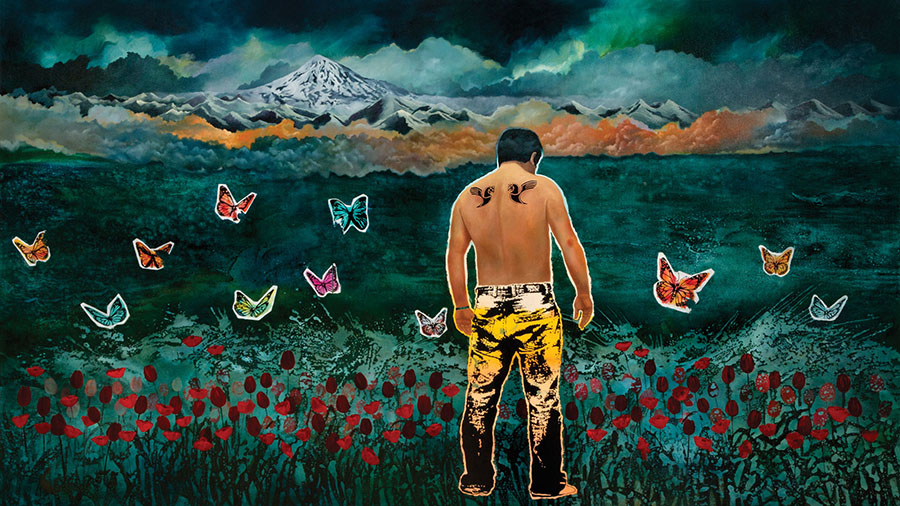

In the video, we witness the artist riding his bike – another childhood toy, like the sticker – until he is exhausted. Children do not usually play to exhaustion. They play to play. Pain in this game. “My grandfather’s house is a metaphor for my country,” Eskandari writes, adding, “cycling around [and around] is both a sign of reverence,” as one does around the Ka’aba, but “also a reference to a useless and vicious circle of life.” In a similar tone, the artist inserts himself into his painterly narrative… into one of his large-scale paintings. As if he offers his own body as a canvas, as a pardeh. He becomes a surface to tell yet another (national) story. In his jeans, Eskandari stands solid yet, instead of look up to the majestic Damavand, he looks down, as if disillusioned, as if defeated. He has wings attached to the anatomical spot where angels grow winds. Yet, the artist does not fly. His wings are mere tattoos. Stickers of the icon of IranAir, a once prestigious national airline that has deteriorated due to lack of replacement parts. The rest of the world is to blame for its economic embargo on the Islamic Republic. Eskandari cannot, is not willing to fly, yet the butterflies surrounding him do. They are made of stickers.

The regular irregularity of our lives, the pain of Iran, and its illusionary dimensions are the undertone of these paintings. Mohamad Eskandari’s soulful and dexterous practice and his ability in depicting ecstasy and agony is exemplary. He has chosen to celebrate and salute his generation and like many of his compatriots he pushes the boundaries in his everlasting search for “Spring”, fluctuating in permanent disorder and chaos but always insisting on hope.

Five vibrant figures, fastened to the canvas “sticker-style” as notes the artist, on at the center of the picture plane. Vibrant. Active. Optimistic. Forward looking. One woman. Four men. At the center stands the captain of Iran’s national soccer team, Ahmadreza Abedzadeh. Confidently walking forward, to the future. Perhaps defining it, shaping it; deciding the nation’s destiny. On this canvas, they, this girl and these boys, seem to be the monuments. They are the nation’s heritage. The red thread that visually, as well as ideologically, combines Eskandari’s five paintings is the rich bed of tulips on the foreground of the picture planes, upon which each visual narrative unfolds. Highly symbolic, they connote the revolution, the war, and the struggles since. As these exquisite paintings imply, it is perhaps no longer possible to tell any story without really evoking those who have, and continue to give their lives for the realization of a fair society. Any story about modern Iran must be implanted upon a bed of red tulips. Standing amid tulips and butterflies, the artist awaits to the day when he can look up.

Talinn Grigor

Boston, May 2015